I.Introduction

As a result of globalization we are now witnessing the rapid increase both of global interdependence and of global risks. Global financial crisis, terrorism, paradox of the humanitarian-military intervention and global ecological risks including climate change and nuclear accidents show us clearly that we are living in the age of global risks.[1] So the demand of a global publicness(公共性) which is hoped to be able to coordinate these interactions and cope with the global risks comes up on the agenda not only of academic but also of global political discussion. Meanwhile, however, it also has become clear that neither the old international law regime nor the global American hegemony regime could meet satisfactorily this demand. Thus there explode various cosmopolitan discourses in various areas to give an alternative answer to this question of new global order.[2]

This paper also belongs to them. In the following, however, we would like to present the profile of 'another' cosmopolitanism through the critical reconstruction of one of the core elements of Chinese political imaginary, the conception of Tianxiaweigong(天下爲公), which means literally: “All under the Heaven belongs to the public.”[3] As is well known, Tianxiaweigong has never ceased to be the core Chinese political imaginary through the long Chinese history. It functioned not only as the regulative idea of Confucian politics, but also was the leading political idea of Sun Wen. The first meaning of ‘another cosmopolitanism’ lies in the fact that it starts not from the main western tradition of cosmopolitanism but from the tradition of Confucian political thoughts.[4]

However it has the second, but more important meaning that is concerned with two deficits which the cosmopolitan publicness in the age of global risks should cope with. The first one is the well- known "democratic deficits" which refers to the fact that global institutions or organizations fall shorts of democratic principle of legitimacy.[5] The second one is what we would like to call ecological deficits. As will be discussed later, the cosmopolitan order in the age of global risks needs the reflective publicness in its dual meaning to cope with both two deficits. As a metaphor of this reflective publicness we can imagine a ship of global democratic publicness on the wavy ecological sea. To explore the meaning of this metaphor would be equivalent to exploring the second meaning of the ‘another cosmopolitanism’.

We would like to proceed in the following way. First, we would like II) to reconstruct the structure of the cosmopolitan publicness contained in Neo-Confucian conception of Tianxiaweigong in the form of the grammar of Confucian publicness, and III) will discuss the three paths of reconstructing the Heavenly Principle in the name of the dialectic of Confucian enlightenment, and based on this critical reconstruction will presents the profile of the eco-democratic publicness as the critically reconstructed Neo-Confucian cosmopolitan order. Lastly we will IV) explain its reflective structure in its dual sense and explore its implication for our age of global risks.

II. Grammar of Confucian Publicness: A Reconstruction of Neo-Confucian conception of Tianxiaweigong (天下爲公)

When the term Tianxia(=All under the heaven) first appeared in political scene in the Zhou dynasty, not only it referred to the political-geographical world as the region of the political rule but also it contained a conception of political legitimacy based on Tianming(天命, Mandate of Heaven).[6] It meant the public and fair world which is governed by the legitimate ruler who received the Mandate of Heaven. In this sense Tianxia meant literally the cosmo-political order. And Tianxiaweigong sums up this cosmo-political idea in that it is composed of the Tianxia as the politically constituted world and the heavenly publicness as the source of legitimacy. Here Tianming mediates between Tianxia and the heavenly publicness and functions as the normative criterion for both justifying and criticizing the Tianxia as the really existing political world order. In this respect, the cosmopolitan order implied in Tianxiaweigong is neither the purely utopian moral idea irrespective of the actual world nor the real political word order without any transcending moment. Rather it has played critical function in the real historical world as an immanent-transcendent publiceness. In this sense we can say that the cosmopolitanism implied in it has the characteristic of actual utopianism.

It has another significant feature that it is based on the articulation of the political and the cosmological. First, Tianxia (天下) embraces not only human beings but also all non-human existences. Second, the publicness which has the role of organizing and justifying Tianxia is derived from the cosmological order. In this sense we can say that the cosmopolitan order of Tianxiaweigong is embedded in the natural order. In other words, the cosmopolitan publicness as political order is embedded in the cosmological order, something like the ship on the sea.

We think that these two structural features of the cosmopolitanism implied in Tianxiaweigong have important implications for reconstructing the reflective global publicness in its dual sense. We will discuss them later in section IV. Before it, however, it is required to reconstruct the Neo-Confucian grammar of publicness.

Though Tienxiaweigong continued to be the core of the Chinese political imaginary, it was only in Neo-Confucian conception of it that the various dimensions of its publicness were differentiated and at the same time internally related so that a complex structure which we would like call the grammar of Confucian publicness was formed. We think therefore that this grammar can be understood as that of Neo-Confucian cosmopolitan publicness.

This grammar was formed as the result of the project of Confucian enlightenment politics in the Sung Dynasty. And this project emerged as a synthesis of Neo-Confucian enlightenment thoughts and the Chinese political concept of Minbon(民本). This synthesis became possible with the paradigm shift from the Mandate of Heaven(天命) to the Heavenly Principle (天理). As is known widely, the Mandate of Heaven was the principle for legitimizing and criticizing political authority from the Zhou Dynasty. But the receiver of the Mandate was confined to the King, and there was no real separation between political power and its justifying principle. As a result the Mandate of Heaven functioned rather as a legitimizing ideology than as the criticizing principle. But Neo-Confucianism expanded the Mandate addressee, extending it not only to the throne but to all human beings. The first sentence of The Doctrine of the Mean on which Neo-Confucian teachers paid particular emphasis summed up this change: "The Mandate of Heaven is called Human Nature"(天命之謂性).

The legitimizing principle then no longer lay in the Mandate of Heaven bestowed upon a dynastic founder and passed down through the royal line, but was located in every human mind as a moral potential. Political power and moral principle of its legitimacy were now separated into distinct entities. In other words, the lineage of kingship was now separated from that of Tao. With this separation was launched the (Neo-)Confucian enlightenment politics that sought to actualize the separated moral demands of the Heavenly Principle(天理) in the 'All under the Heaven'(天下) as the socio-political world.[7] In this sense, this project of Confucian enlightenment politics may be also understood the Neo-Confucian cosmopolitan project to constitute Tianxia as the cosmopolitan public order.

This cosmopolitan order was composed of four dimensions of publicness which are internally connected with each other by the project of the Confucian enlightenment politics. The first dimension of Tianxiaweigong is the publicness of Heavenly Principle. Here we would like to limit ourselves to present some characteristics of it. When Neo-Confucian teachers interpreted the Heavenly Principle, they were used to refer to the famous sentence from Book of Change: "The successive movement of yin and yang constitutes the Way(Tao)." They understood Tao as the dynamic principle of the cosmological synthesis of vital forces, put in modern terms, as the principle of autopoietic process of cosmological life. In this sense the publicness of the Heavenly Principle was in essence a meta-biological and cosmological one.

The main characteristics of this cosmological publicness can be summed up as its openness, fairness, cosmological communication and sympathy. Cheng Hao(1032-1085), one of the founding fathers of Neo-Confucianism, grasps this explicitly.

"The constant principle of heaven and Earth is that their mind is in all things, and yet they have no mind of their own. The constant principle of the sage is that his feelings are in accord with all creation and yet he has no feelings of his own."[8]

"A book on medicine describes paralysis of the four limbs as absence of jen (仁, Humanity). This is an excellent description. The man of jen regards Heaven and Earth and all things as one body. To him there is nothing that is not himself. Insofar as he recognizes all things as himself, can there be any limit to his humanity? […] To be charitable and to assist all things is the foundation of a sage." [9]

The first task of the Confucian cosmopolitan politics is to limit the arbitrariness of the sovereign power with the help of the Heavenly Principle. How to control the arbitrariness at the center and summit of the bureaucratic state publicness organized by law, the second dimension of the Confucian publicness? After the Qin Dynasty(BC 221-BC 206), this was the central problem in Confucian politics characterized by the merging of Confucianism and Legalism(儒法結合). The publicness of the Heavenly Principle was the Neo-Confucian answer to this question.[10]

Neo-Confucian enlightenment politics had also the positive task of actualizing the moral potential extended equally to all human beings by the Heavenly Principle; in other words, to implement the "publicness of the Heavenly Principle" socio-politically. Integrated with Confucian Minbon politics which reads the heavenly mind in people's mind, this positive task was to be carried out in the area of people's life(民生) and opinion(民意).

The publicness that emerged from the actualization of the Heavenly Principle within the dimension of popular livelihood was based on the political ideal of the Great Harmony(大同). This third dimension of the Confucian publicness, combined with Confucius' notion of justice which was more concerned about unevenness than about insufficiency, may be termed 'Minbon publicness'(民本公共性), which means the 'social justice' in current terms. Its keystone is to guarantee the material conditions for actualizing the potentials of the moral life which the Heavenly Principle accords equally to all human beings.

However, in what procedure is this enlightenment politics deployed? How to know the Heavenly publicness which is to be realized? How to read the heavenly mind in people's mind? Answering this question, Confucian politics invented the Confucian deliberative politics(公論政治), which had the task of justifying and criticizing political authority and actual politics based on a rational core of people's opinion that was discovered and articulated through public deliberation. We call the publicness formed in connection with this task 'deliberative publicness'(熟議公共性).

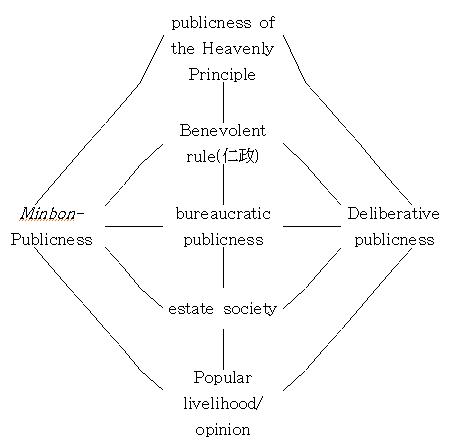

In sum, the publicness of the Heavenly Principle regulates the arbitrariness internal to state-bureaucratic publicness and at the same time realizes itself by means of dual mechanisms of the Minbon- and the deliberative publicness. This is the grammar of Confucian publicness. (Figure 1). As the idea of Tianxiaweigong developed into Neo-Confucian enlightenment politics with the paradigm shift from the Mandate of Heaven(天命) to the Heavenly Principle(天理), the structure of the cosmopolitan public contained in that idea also developed into this grammar of the Confucian publicness.

Figure 1) The grammar of Confucian publicness as the grammar of Neo-Confucian cosmopolitan publicness.

III. Dialectic of Confucian Enlightenment and Grammar of the Eco–Democratic Publicness.

1) However, it would be unreasonable to infer directly from this grammar the configuration of the cosmopolitan publicness in the 21C, because it was restricted by the pre-modern social and intellectual conditions. The democratic task of our times is concerned about how to establish a deliberative Minbon publicness(熟議的 民本公共性), as the core of the grammar of Confucian publicness, under the contemporary conditions. In this regard, the Heavenly Principle as a meta-biological and cosmological one gives us deep ecological inspirations. We would like to explore, therefore, whether the grammar of Confucian publicness can provide us a normative direction and language for a eco-democratic publicness both in the national and global context. However, these eco-democratic implications could not be automatically realized given the proper social conditions alone. The grammar of Confucian publicness, above all the Heavenly Principle, must first be critically reconstructed for those eco-democratic implications to gain feasibility in the 21C, just as the establishment of the Confucian grammar of publicness was possible with the shift from the Mandate of Heaven to the Heavenly Principle. To deal fully with this reconstruction, however, would require a separate treatise, and such is not the purpose of the present one. Here we limit ourselves to showing briefly the possible paths of reconstructing the Heavenly Principle.[11]

The first point to be considered is that though this reconstruction is not one of actual historical paths, nonetheless it is not arbitrary one but a rational reconstruction of the potential developmental paths latent in Confucian enlightenment politics. To express this point we will call this reconstruction a dialectic of Confucian enlightenment. This dialectic refers to the entire process in which the Heavenly Principle encounters -in the course of its realization in society- social practices, whereby the Principle is pressured to change, and the reconstructed principle once again sets in motion politics of enlightenment, which results in new grammar of Tienxiaweigong.[12]

Can this dialectic, however, be supported from within Confucian thoughts? We think so because it stems from the very project of Confucian enlightenment politics. As already pointed out, this politics saw as its task the social realization of the publicness of the Heavenly Principle. In relation to this task, the Heavenly Principle encounters social practice, and from this encounter emerges a dialectics of enlightenment which transforms the Heavenly Principle itself. In this sense we can say that the dialectic stems from Confucian enlightenment politics itself.

The second reason can be found in Confucius' own thoughts. The Master said: “It is human beings who are able to broaden the Way, not the Way that broadens the human beings.”[13] If human beings are to broaden the Way, the Way must be located in human practice, not outside of it. And it means that the Way broadened through human practice can be understood as an expression of human autonomy. So it is not enough for the Heavenly Principle to be realized in the society. It is required that it should be located in social practices and be reconstructed from within them. And this reconstruction faithful to Confucius' conception of the Way would change the grammar of Confucian enlightenment politics. In this sense it is to be understood not as a deviation from Confucian thoughts, rather as a critical return to Confucius' thoughts itself.

2) The critical reconstruction/transformation of the Heavenly Principle and the dialectic of Confucian enlightenment may be carried out in three paths. The first one is the materialistic path, in which the Heavenly Principle is reconstructed from within the productive and reproductive social activity in relation to the Minbon publicness. Historically, the first clear signs of this path appeared in the late Ming and early Qing with the affirmation of the private(私), coming to fruition in Tai Chen's concept of jen (Humanity, 仁). Tai Chen(戴震:1723-1777) said:

"To desire to preserve and fulfill one's own life and also to reserve and fulfill the lives of others is jen (humanity). To desire to preserve and fulfill one's own life to the point destroying the lives of others without any regards is the absence of jen (inhumanity: 不仁)"[14]

As we said before, Neo-Confucians understood jen (Humanity) as the principle of cosmological communication within the framework of human/cosmos in contrast to the western framework of human/God. It was now re-interpreted by Tai Chen as the principle which not only operates for social practice but also resides in it.

It is easy to see how this materialistic conception of jen, reconstructed in the context of Minbon publicness, could develop into the socialist project in China. In spite of different orientations within this project, they are common in that they were primarily concerned with the material productive activity and welfare. The Chinese socialist path to the first modernity might be understood as a form of the Confucian dialectic of enlightenment. If so, what does the failure of the so-called "really-existed socialism" means in our context? We think that the materialistic path and the Minbon publicness alone are not enough for designing and establishing the grammar of Tienxiaweigong in the 21C.

3) The second path may be called a discursive path, in which the Heavenly Principle encounters public deliberation in the dimension of popular opinion(民意). How can we think of this path within the project of Confucian enlightenment politics? The Heavenly Principle which should be realized through Confucian politics remains unspoken. However, the popular mind(民心), the only possible medium for its expression, is precarious. This situation necessitates a 'mean'(中) adopted between the unsaid "Heavenly Principle" and the precarious popular opinion. But how to adopt such a 'mean'? As we said before, for Neo-Confucian politics, the answer to this question was Gongnon(公論), the public deliberation. Here, adopting the 'mean' does not mean simply taking a middle position, but discerning the rational core contained in the precarious popular opinion. This is achieved through public deliberations. So public deliberation is the locus where the Heavenly Principle encounters with popular opinion. This is also evident in Zhu Xi's definition of Gongnon, namely, "that which follows the Heavenly Principle, accords with the people's mind, and is held as true by all."[15] We can then say that the task of Confucian deliberative politics is to discern the Heavenly Principle, the rational core of popular mind and opinion, and realize it in the society.

If so, the Heavenly Principle may be under the pressure of change from within the social practice of public deliberation in the dimension of the deliberative publicness, just as jen was so in the dimension of the Minbon publicness. If this could result in transforming the Heavenly Principle into the principle of the social communication and public deliberation, it might be called the linguistic return to Confucius.

In contrast to the material path, this discursive path did not appear (nor was it perceived) with any clarity in the pre-modern Confucian society. But we need not negate this potential developmental path because deliberative politics was flourished in Joseon dynasty of Korea. Deliberative politics was not confined simply to state publicness. Rather, it cut across the boundaries of the state, and -although limited by the pre-modern estate society- expanded and deepened into society to become a strong check on state bureaucratic publicness.[16] This historical fact shows that the potential of deliberative politics exists (or at least needs not be negated) in the Confucian dialectic of enlightenment. The Heavenly Principle may then be reconstructed, for example, as a discursive rationality inherent in linguistic communication and regulating public deliberation. Furthermore, a new political project might be set in motion to realize this rationality. In this sense, we may speak of the grammatical possibility of a shift from a Confucian publicness to the democratic deliberative publicness. In a sense, the Korean path to democracy may be construed as a delayed realization of this grammatical potential.

4) We have discussed so far two possible paths for the dialectic of Confucian enlightenment. Through these two paths the Heavenly Principle is transformed from the cosmological principle to social principles. This means that its social synthesizing function is transferred from the Heaven to such social practice as social labor and public deliberation and to the rationality reconstructed from within them. What is then the fate of the Heavenly Principle as a meta-biological and cosmological one? With respect to this question we can think of an ecological path of our dialectic. This path has become already actual in view of the ecological crises that threaten humanity and the pressing demand of establishing a global ecological publicness.

This ecological path is based on the category of life-giving process, the autopoietic process of cosmological life. Though life-process is the very base of our social life, there are always some residues which manifest itself mainly in the negative form of various ecological crises without being synthesized into the realm of the social.

This makes the ecological path distinct from the first two paths. While the two paths are located within social communities even in its cosmopolitan form, the ecological path deploys itself throughout the inside and outside of the cosmopolitan community. While the two paths promote actively the dialectic, this third path does so mainly in the negative form of ecological crisis. While the two paths appeared first in the context of nation state of the “first modernity”(U.Beck) and then are moving into the global context of the second modernity, the ecological path proceeds from the start within the global context and compel us to take the cosmopolitan perspective.

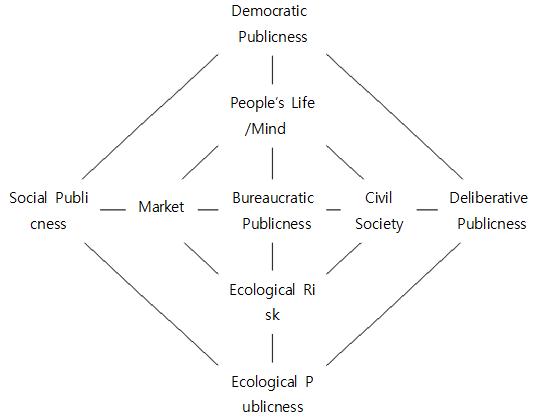

Now let's summarize the results of these three dialectical paths. They can be summed up in <Figure 2>, where the bureaucratic publicness is surrounded by the deliberative, the ecological, and the Minbon publicness in relation to the structural differentiation of state, market, civil society and the ecological horizon. We would like to call it the grammar of eco-democratic publicness. This grammar can operate both in the national and in the global context. In national context, this grammar shows that individual nation state has the task of establishing three publicness which are respectively connected to global market, civil society and ecological environment. In this case, it functions as the grammar for "responsible cosmopolitan state".[17] However, for this "responsible cosmopolitan state" not to be confined to a few global powers, it is required to establish global eco-democratic publicness which is able to cope with such global risks as the global economic crisis, terrorism, and global ecological risk without falling into the trap of 'democratic deficit' and ecological deficit.

Figure 2) Grammar of the Eco-Democratic Publicness

IV. A Ship of the Eco-Democratic Publicness on Wavy Ecological Sea

This grammar of global eco-democratic publicness can be understood as that of the Tianxiaweigong in the 21Cy. This is the shape of the ‘another cosmopolitanism’ in its first meaning. Now it is time to explore its second meaning.

As we said earlier, the global publicness in the age of global risks has two tasks, the democratic one and the ecological one, which respectively corresponds to the democratic deficit and ecological deficit. From the viewpoint of our ‘another cosmopolitanism’, the democratic task may be summarized as the following demands: the pursuit of the welfare-oriented Minbon publicness should be supplemented and regulated by the deliberative publicness. Here ‘democratic deficit’ refer not only to the lack of democratic legitimacy in the dimension of deliberative publicness, but also to the enormous socio-economic inequality caused by the neoliberal globalization in the dimension of the Minbon Publicness. Thus to cope with these democratic deficit, the pursuit of the welfare-oriented Minbon publicness should be supplemented by the deliberative publicness. In fact, it would be extremely difficult to regulate the unleashed movement of global market without help from the global deliberative publicness. Furthermore, global publicness including Minbon publicness should be carefully designed for it not to injure both the individual autonomy of human beings as world citizen and the autonomy of the collective form of life. It is thus necessary for them to be monitored and regulated by global deliberative publicness. To put it simply, establishing a global deliberative Minbon publicness is the primary democratic tasks of the Tianxiaweigong in the 21C.

From its viewpoint, ecological task has an ambivalent character. On the one hand, solving ecological risks also belongs to democratic tasks because they should be solved in the way that can satisfy demands of the deliberative Minbon publicness. Satisfying the demand of the Minbon publicness means that the ecological justice should be established both in the national and in the global context. And to satisfy the demand of the deliberative publicness, citizens should be able participate in interpreting and solving ecological risks, because, as U. Beck emphasizes, the risk does not exist as naked one but as the interpreted and constructed one. This is the necessary condition for solving ecological risks democratically.

On the other hand, however, the solution of ecological risks does not exhaust in establishing the deliberative Minbon publicness. As we said before, there remains always the residual ecological dimension which functions as a ecological horizon and cannot be subsumed into the eco-democratic publicness. For instance, one may ask: is there an inherent moral value in nature which should be respected irrespective of the human beings' interests? We cannot discuss here this complex issue in detail. Instead, we would rather to present the relationship between the eco-democratic publicness and the ecological horizon from the viewpoint of Tianxiaweigong in the 21C.

In Confucian political tradition there comes down a political metaphor to view the relationship between the state and people as a ship on water. To use this metaphor, we can view the ecological horizon as the stormy sea and the eco-democratic publicness as a ship on that sea. We think this may be a pertinent image of the cosmopolitan publicness in the age of global risks.

In the age of the industrial modernization, risks were regarded as what could be well calculated and managed. However, as Fukushyma nuclear accident clearly showed it, the ecological disasters that could destroy totally the modern risk management system remains no longer in the shadowy dimension of possibility. Ecological disasters remain no longer as the typhoon in the teacup of the modern risk regime. Rather the contemporary society is now like a ship shaking on the wavy ecological sea where the typhoon of ecological disaster is coming closer. The transition from industrial society to risk society means the inversion of the managed ecological risk within teacup of the risk management system into the risk management system shaking on the sea full of ecological risks. Those who continue to be attached to the anachronistic belief of the modern risk regime could not avoid being drowned by the sea of ecological disasters.

However, the green romanticist's advise to abandon the ship of the (eco-democratic) publicness and plunge into the ecological sea is a rough-and-tumble response which would lead to the same result.[18] They think that the modern society cast on the ecological sea could not avoid being drowned by the sea, because they think that the ship of modern society is only made of the iron. However, they does not imagine that the ship may be made of woods, and therefore may not be drowned by that sea even though it may tremble on that stormy sea. This is a pertinent image of Tienxiaweigong reconstructed in the 21C. However, even Neo-Confucian grammar of publicness also might be drowned by the sea of ecological disasters, if its Heavenly Principle be not reconstructed in the paths of the dialectic of Confucian enlightenment.

When the Heavenly Principle is reconstructed all in its three paths, the ‘Principle’ of the ‘Heavenly Principle’ is transferred into the space of social practice and comes to be in the form of the organizational principle of the global deliberative Minbon publicness. In what mode then does the ‘Heaven’ deprived of its synthesizing function continue to be? It may exist in two modes. On the one hand, it may exist in the mode of the global dimension of the eco-democratic publicness. In other words, it may reside in the demand that the deliberative, the ecological, and the Minbon publicness should be established not only in national dimension but also in the global dimension. On the other hand, the Heaven may exist now in the mode of the ecological sea on which the global eco-democratic publicness is floating.

Here we can see that Tienxiaweigong of the 21C has the reflective publicness in its dual sense. On the one hand this ship Tienxiaweigong should establish its own democratic structure which requires a reflective relation to itself mainly on the dimension of the collective decision. We may call it democratic reflectivity which is constitutive of the eco-democratic publicness. On the other hand it should keep a reflexive relation to the ecological sea, in which it encounters unintended, uncontrolled negative consequences of its collective decision. We may call it ecological reflexivity. For the ship to avoid both the democratic and the ecological deficits, two kinds of reflective relations should be adequately mediated without being reduced to each other.

Here public deliberation on ecological risks may play the role of mediator. It can mediate between the deliberative Minbon publicness organized by the discursive rationality and the ecological risk which is discursively interpreted and constructed. At the same time, it allows the ship of the global deliberative Minbon publicness feel its negative effect on the ecological sea in its trembling. Keeping its ecological reflexivity in this way, the eco-democratic publicness, though trembling on the wavy ecological sea, nevertheless does not sink into that sea. Furthermore, in the same way, it can transform the enormous energy of the wavy ecological sea into the energy for expanding the global eco-democratic publicness.

The significance of this reflective structure of the cosmopolitan publicness would be more clearly grasped, if we compare it with cosmopolitan projects of J. Habermas and U. Beck which help us to reconstruct ‘another cosmopolitanism’. Though they are clearly conscious of two deficits of current global publicness, it seems that they respectively put emphasis on solving one of the two deficits. Habermas pays attention mainly to solving the ‘democratic deficit’, and suggests the project of constitutionalization of international and global relation through the cosmopolitan law. Though, of course, the ecological deficit may be solved in part within the eco-democratic publicness, it seems that this approach does not pay due attention to the relation of the ship of the eco-democratic publicness and the ecological sea. In his project, public deliberation mediates mainly between System and Life-world, not between the Society in general and the ecological horizon. It serves not to the ecological, external reflexivity but only to the democratic, internal reflectivity.

In contrast, Beck puts emphasis on the ecological deficits[19] in his cosmopolitan project and suggests the idea of ‘emancipatory catastrophism.’[20] He pays much more attention to the ecological reflexivity than to the democratic reflectivity. He emphasizes the emancipatory political energy of the ecological catastrophe more than the enlightenment project to institutionalize the normative principle. However it is unclear in what way and in what form would the energy be institutionalized into the public order. He seems to hope that it could be the main sources of global solidarity necessary for global democracy project. Of course it could be so. However, it could also be oriented to the ecological totalitarian regime under the banner of the eternal ecological state of emergency.

In this comparison we can see easily that the reflective global publicness in its dual sense which is required to solve both the democratic and the ecological deficit is bifurcated respectively in contrary direction in their projects. In contrast to them, Tienxiaweigong (天下爲公) in 21C shows us how to construct and preserve such reflective global publicness. Here we may find the most important significance of this ‘another’ cosmopolitanism for our age of global risks.

[1] Ulrich Beck, Weltrisikogesellschaft, Shurkamp, F/m, 2007.

[2] David Held, Cosmopolitanism Polity Press, Cambridge, 2010; U. Beck, Cosmopolitan vision. Cambridge, Polity Press, 2006; U. Beck and N. Sznaider, "A literature on cosmopolitanism: an overview", in The British Journal of Sociology , 2006 Volume 57, Issue 1; D. Archibugi, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. 2008; J. Habermas, "Plea for a constitutionalization of international law", Philosophy & Social Criticism, 2014, 40(1), pp 5-12. Gerard Delanty(ed), Routledge Handbook of Cosmopolitanism Studies, Routledge, New York, 2012.

[3] 陳澔(編), [禮記集設大全, 禮運] (鄭秉燮 譯) 學古房, Seoul, Korea, p.38.

[4] The most widely known case of it may be Zhao, Tingyang, Tianxia Tixi: An Introduction to a Philosophy of World Institution, Nanking, 2005; ‘Rethinking empire from a Chinese concept “All-under-Heaven” (Tianxia), Social Identities 12(1), 2006, pp. 29-41; "A political world philosophy in terms of all-under-Heaven (Tianxia)", Diogenes 221, 2009. pp. 5-18.

[5] J. Habermas, ibid, 2014

[6] Chang Chishen “Tianxia system on a snail’s horns”, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Volume 12, Number 1, 2011. pp. 30-31.

[7] K. Bol, Neo-Confucianism in History, Harvard Univ. Press, 2008.

[8] A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy (ed. and tr, by Wing-Tsit Chan), Princeton Univ. Press, 1963, p. 525.

[9] Ibid., p.530.

[10] This is also a Confucian method for solving the paradox of sovereignty. On the relationship of the paradox of sovereignty and Confucian politics, see Park, Young-Do, “King Sejong's Confucian Rule by Law", in Review of Korean Studies, Vol. 9, No.3 (September, 2006), pp.103-132, esp. pp. 105-110; "Paradox of Sovereignty and the Grammar of Confucian Publicness", in 『Society and Philosophy』, Vol. 27. Seoul, 2014. pp. 139-168.

[11] About the nature of the Heavenly Principle, its problems, and the general direction of its critical reconstruction, see Park, Young-do, "Reconstruction of Neo-Confucian Concept of Rationality“,『Korean Studies Quarterly』, vol. 24, no. 1 (Spring, 2001), The Academy of Koreans Studies, pp. 141-178.

[12] In this sense, this dialectic is closer to Habermas' conception of dialectic of enlightenment than to the negative one of Adorno and Horkheimer.

[13] “子曰 人能弘道 費道弘人”. [論語], 15, 28.

[14] 戴震, “欲遂其生 亦遂人之生 仁也. 欲遂其生 至於戕人之生而不顧者 不仁也”, [孟子字義疏證], Hongik Press, Seoul. 1998, p. 218; Tai Chen, Commentary On The Meanings of Terms in The Book of Mencius, in A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy (Tr. and Ed. by Chan Wing-Tsit), Princeton Univ. Press. 1 969, pp. 713-714.

[15] “順天理 合人心 而天下之所同是者”, [朱子大全], 卷 24. <與陳待郞書>.

[16] On the Gongnon politics of Joseon Dynasty, see 薛錫圭,[朝鮮時代 儒生上疏와 公論政治], Seonin, Seoul, 2002.

[17] Garrett Wallace Brown "Bringing the State Back into Cosmopolitanism: The Idea of Responsible Cosmopolitan States", in POLITICAL STUDIES REVIEW , 2011 VOL, 9, pp.53-66.

[18] On Green Romanticism, see John S. Dryzek, The politics of the Earth, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2005, pp.183-201.

[19] U. Beck, Cosmopolitan Vision, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2006.

[20] U. Beck [Emancipatory Catastrophism], Public Lecture at “The Seoul Conference 2014 with Ulrich Beck,” July 8, 2014. pp. 33-47.